The original paper is included in IEEE ICBC 2024 proceeding, view or cite it: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10634335.

Preprint PDF:

Poster:

Abstract — Decentralized Finance (DeFi) has emerged as a transformative force in the financial landscape, bringing about challenges in ensuring blockchain security. This paper systematically examines prominent DeFi incidents from June 2022 to May 2023. Our findings underscore the significance of continuous vigilance in DeFi operations.

Introduction

Blockchain technology possesses many powerful features such as decentralization, persistence, anonymity, and auditability. These features enable the emergence of innovative applications such as decentralized finance (DeFi), decentralized autonomous organizations (DAO), decentralized identities (DID), and more.

The features of DeFi have attracted a substantial influx of capital. In April 2022, the total value locked in DeFi reached a peak of 200 billion USD. Despite experiencing a significant decline afterward, as of April 2023, the total value locked in DeFi still amounts to a substantial sum of 49 billion USD.

However, the high level of transparency and anonymity in DeFi also provides attackers with opportunities to exploit capital. In March 2023, Euler Finance, a decentralized lending protocol, suffered an attack that drained cryptocurrencies equivalent to 197 million USD. Notably, up to 6 auditing firms were partnering with Euler Finance, yet none of them identified vulnerabilities resulting in this incident. This indicates that the DeFi industry still faces security challenges.

Despite previous efforts to systematically classify DeFi incidents, as well as develop scanning tools to detect vulnerabilities, DeFi incidents continue to arise frequently. We systematically categorized DeFi incidents from June 2022 to May 2023 based on prior studies. Then, we selected several scanning tools to scan these vulnerable contracts and verify whether these existing scanning tools can effectively identify vulnerabilities before attacks occur.

Analysis of Vulnerabilities

Despite many academic institutions and businesses conducting systematic analyses, there is currently no globally accepted standard for classifying blockchain vulnerabilities and attacks. This is because blockchain technology has been evolving rapidly, and new vulnerabilities and attack methods are constantly emerging, making it difficult to devise a complete and comprehensive classification standard.

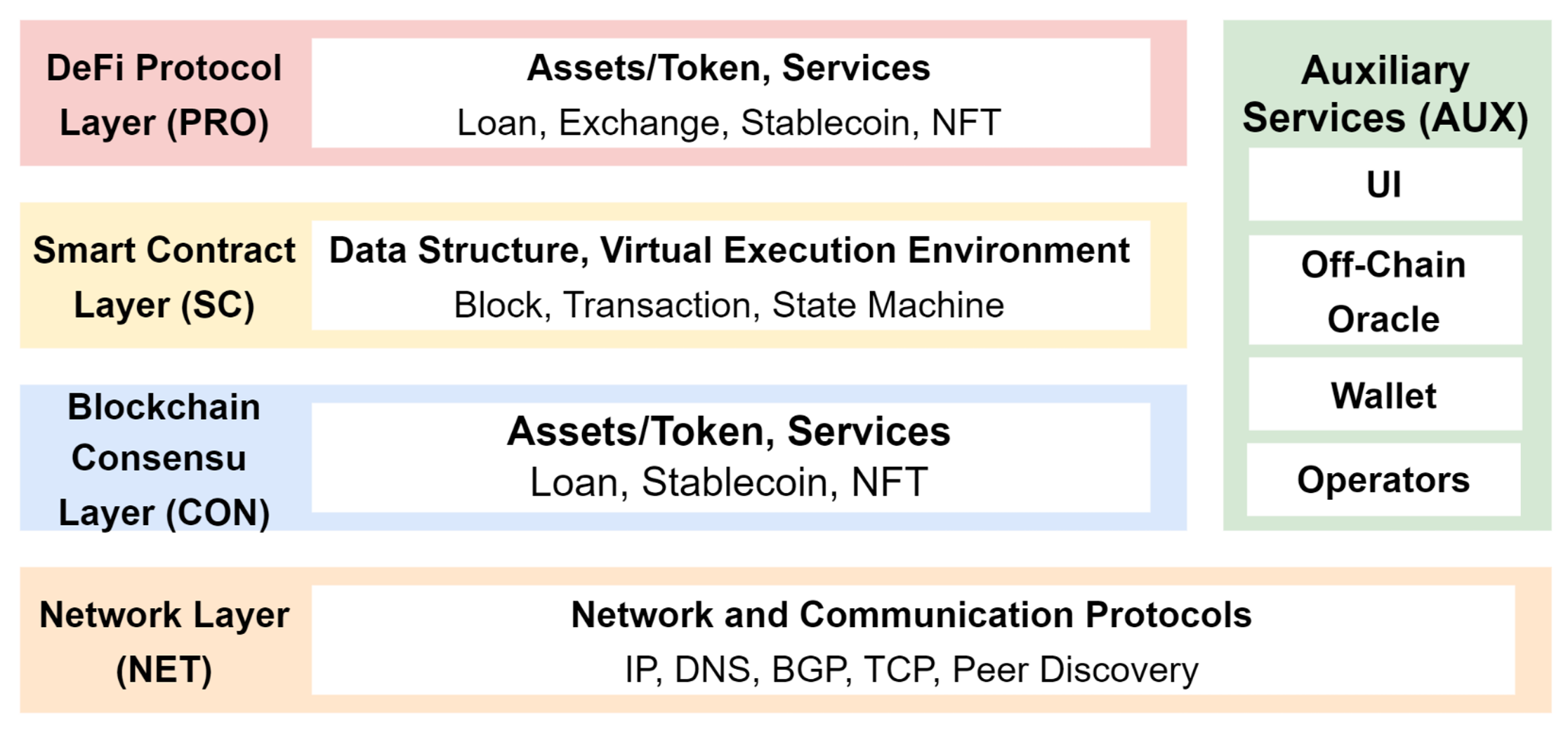

After a thorough review of research papers, the 5-layer framework proposed by Zhou, Liyi, et al. “Sok: Decentralized finance (defi) attacks” 2023 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy presents the most comprehensive coverage of all vulnerabilities in blockchain, shown in the following table. We have opted to utilize this framework to categorize the vulnerabilities in DeFi, as it enables a more comprehensive and precise analysis.

A. Network Layer (NET)

In the Network Layer, nodes communicate by transmitting messages through various network protocols, such as TCP/IP and DNS. Common incident types in this layer include:

1) Network Transparency: Exposing transaction data to the public network could provide attackers with the opportunity to create counterfeit transactions. Blockchain systems should create secure TLS connections to miners, and confidentially share all credentials.

2) Improper Peer Discovery: Peer-discovery may expose the location and identity of nodes, enabling attackers to pinpoint nodes, such as eclipse attacks. Attackers may also abuse poorly designed peer discovery algorithms to launch denial of service attacks.

3) Network Congestion: This usually refers to denial of service attacks.

4) Exposed Internet Services: A blockchain system must secure network access services to prevent BGP hijacking and DNS hijacking. This incident cause was first observed in an attack against MyEtherWallet. Due to a BGP flaw, an attacker can announce ownership of any prefix to its neighbor routers to redirect users to a fake website and compromise victims’ private keys.

Consensus Layer (CON)

The Consensus Layer is used to determine which transactions are included in a block and to ensure the consistency and security of the blockchain. There are multiple algorithms for the Consensus Layer, such as Proof of Work (PoW) in Bitcoin, and Proof of Stake (PoS) in Ethereum. Common incident types in this layer include:

1) Unstable Incentive Mechanism: Incident types in this category are quite diverse. All of them are enumerated below with brief explanations.

- Majority / 51% Attack: When a group of nodes controls over 50% of the total computing power of a blockchain, it allows them to rewrite blocks. Even if the group controls lower but close to 51%, they still have chances to overwrite blocks.

- Block Reorganization: When a block is removed from the blockchain due to a longer chain being discovered, it results in the loss of previously confirmed transactions. During the reorganization, attackers may exploit the asynchrony of information to launch attacks.

- Selfish Mining: A group of miners solves a hash, creates a new block, and keeps it hidden. This creates a fork, which is mined to surpass the public blockchain. If the group’s chain outpaces the honest one, they overwrite the original blockchain.

- Double Spending: A user attempts to spend the same cryptocurrency twice. Though consensus algorithms prevent spending multiple times, this can occur in a majority / 51% attack.

- Feather Forking: A small group of nodes creates its own version of the blockchain. For instance, the group refuses to build on any chain that contains a block with the unwanted transaction. As long as this group has the longest fork path, all other honest miners may have a chance to include the forked chain in the main chain.

- Bribery Attacks: Bribe miners to manipulate blockchain consensus or transaction order, leading to attacks such as double spending, historical alterations, transaction delays, etc.

- Mining Difficulty Adjustment: Manipulating the rate of block creation.

2) Unfair Sequencing: The attackers alter the sequencing of transactions to gain a favorable price. Or, they censor and obstruct the transactions of other users.

Smart Contract Layer (SC)

Smart contracts are programs stored on blockchains to execute automatically when predefined conditions are satisfied. These conditions are typically based on the terms of an agreement or a specific workflow. In essence, smart contracts serve to eliminate the need for third parties or intermediaries in transactions.

The smart contract layer allows for the creation and deployment of smart contracts, enabling transaction-level atomic state transitions and storing various states of the blockchain system, such as users’ cryptocurrency balances, cryptocurrency addresses, block numbers, and other relevant information. The most popular programming language for writing smart contracts is Solidity.

1) Untrusted Or Unsafe Calls: Smart contracts typically use external calls to interact with other smart contracts, external data sources, or users to achieve more complex functionality. However, this provides attackers with opportunities to embed malicious code logic.

- Reentrancy: Repeatedly calling a function within a smart contract before the initial function call is completed.

- Delegate Call / Code Injection: Delegate call is a low-level mechanism in Solidity that permits one contract to execute the code of another contract within the current context. This implies the data and state are shared with the called contract, potentially allowing attackers to bypass authorization checks or modify the state.

2) Coding Mistake: This refers to technical errors made by developers during the coding process, resulting in incorrect smart contract behavior, as opposed to design issues.

3) Access Control Mistake: Attackers utilize external calls, fallback functions, forged wallet addresses, etc. to bypass identity verification. Smart contract developers must ensure that resource access is properly authenticated by any means.

4) State Transition Design Mistakes: Each opcode supported by the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM) is associated with a specific gas cost. These gas costs are designed to reflect the underlying resources consumed by each operation on the nodes that constitute the Ethereum network. A mismatch between the cost of an operation and the actual resource consumption (such as CPU time and memory) has several implications. It can be exploited for malicious purposes such as excessive block processing times and skewed block gas limits.

Protocol Layer (PRO)

The protocol layer is a collection of standardized DeFi protocols that define basic rules to manage cryptocurrency. For instance, ERC-20 establishes the fundamental functionalities of cryptographic tokens, including token transfers, balance inquiries, and approvals. This means that despite belonging to different DeFi projects, all ERC-20-compliant tokens are compatible with each other, which promotes interoperability between DeFi protocols.

1) Transaction Order Dependency Mistake: An agent can benefit from front-running by gaining early knowledge of pending transactions and strategically setting a higher gas fee to prioritize their own transaction execution before the victim’s transaction. This unfair practice allows the agent to obtain more favorable outcomes while causing losses to other participants. Similarly, in back-running or sandwiching, an agent intentionally places its own transaction orders around the target transaction to manipulate the price.

2) Replayable Design: Replicating a transaction executed on one blockchain to another blockchain. This attack is commonly observed during cryptocurrency forks or when transactions are not specific to a particular chain.

3) Block State Dependency Mistake: Block states such as block.blockhash or block.timestamp can be manipulated by malicious miners, so a contract shouldn’t use block states for decision-making. Neither should they use block states as random seeds.

4) Permissionless Interaction: Victims only constrain the function interface of a contract, without considering how the contract is implemented. As a result, attackers exploit contracts that comply with the accepted ABI interface but contain incompatible implementation logic, causing harm.

5) Unsafe Dependency: The reliance on external protocols or some standards provides attackers with more attack vectors. For example, attackers can exploit the quotes provided by an oracle to manipulate prices. They can also acquire a sufficient amount of governance tokens to propose and execute malicious contract code.

6) Unfair or Unsafe Interaction: Participants can obtain more favorable prices via unfair slippage protection or unfair liquidity. Unsafe or infinite token approval refers to a protocol granting approval for an unlimited or excessively high number of tokens to another address or contract.

Auxiliary Service (AUX)

The functionalities that do not belong to the first four layers are classified as the Auxiliary Service Layer, including website management, code/contract deployment, etc. These services typically do not directly participate in the operation of the blockchain system, but they provide necessary support and management to make the blockchain system more user-friendly. In general, vulnerabilities in the auxiliary service layer are usually caused by backdoors, phishing, or trust in malicious data sources.

Analysis of Attacks

In this section, we introduce the attack events proposed by Li et al., “Security analysis of DeFi: Vulnerabilities, attacks and advances” 2022 IEEE International Conference on Blockchain. Then, we apply these classification systems to the investigated incidents in the next section to better understand the characteristics of these incidents.

Utilization of Flash Loan

Flash loans typically refer to the process of borrowing and repaying funds within a single block, with various transactions intertwined through smart contracts. The borrower first obtains a loan amount by pledging a certain amount of cryptocurrency assets and then using rapid trading, repayment, and other operations to achieve borrowing and repayment of funds, thereby achieving arbitrage.

Private Key Leakage

Attackers either steal or exploit the accidental leakage of private keys from the project team, enabling them to gain unauthorized access to deploy and manage the smart contracts. With these permissions, they have the ability to arbitrarily mint and transfer tokens.

Reentry Attack

Attackers insert malicious code within the “fallback” or other external functions, exploiting the reentrancy vulnerability inherent in such functions. By repeatedly calling functions, the attackers can execute the malicious code multiple times, bypassing the contract’s intended logic and control flow.

Arithmetic Bug

Arithmetic bugs in DeFi applications arise from flaws in mathematical operations and calculations. These bugs can result in inaccurate balances, exchange rates, or reward calculations, leading to financial losses or overpayments.

Analysis of Incidents

We opted to the 5-layer framework proposed by Zhou, Liyi, et al. “Sok: Decentralized finance (defi) attacks” 2023 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, to categorize the vulnerabilities in DeFi, as it enables a comprehensive and precise analysis.

Data Source

The investigation scope of this paper is limited to DeFi incidents that occurred from June 2022 to May 2023, involving direct or indirect losses of 1 million USD or more. The incident data sources primarily rely on (i) Rekt News; (ii) DeFiHackLabs; (iii) Slowmist, and official post-mortem reports. To the best of our knowledge, these data sources provide timely and comprehensive coverage of the reported incidents, ensuring that significant events with losses exceeding 1 million USD are not overlooked.

This paper focuses solely on DeFi incidents. Any incidents involving CeFis (e.g. FTX, Binance), DAOs, or NFTs will not be included in the scope of this paper.

Incidents

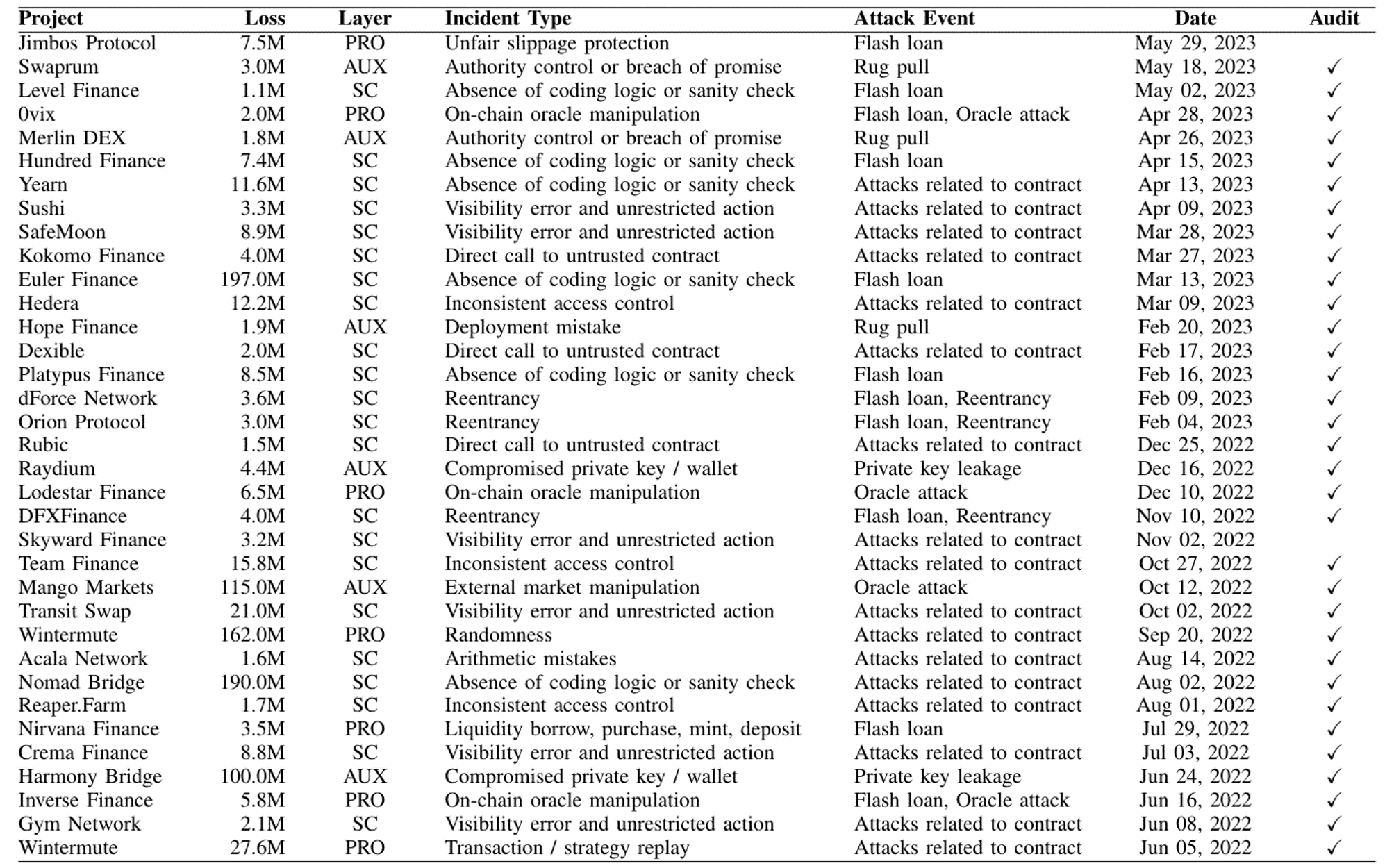

The final result in Table II comprises 35 events, with a total loss exceeding 950 million USD. The table provides information about the loss amount, incident type, whether they underwent professional auditing, occurrence date, and a citation to detailed post-mortem.

Table II reveals that out of 35 incidents, 33 victims had professional audits in place; however, this did not prevent these attacks from occurring. This underscores the need for a more thorough examination of auditing practices and a reevaluation of the factors contributing to the vulnerabilities. Upon an in-depth investigation of 35 case studies, we identified that some incidents stem from the following human errors:

- Leave Audited Risks Unresolved: Quantstamp audit suggested Nomad Bridge validate the

_leafinput of theReplica.sol:prove, with QSP-19 Proving With An Empty Leaf. But the Nomad team seemed to misunderstand the issue and leave it unresolved. - Deploy New Code Without Audit: Gym Network releases new features without being extensively audited. Dexible only had their experienced engineers review new contracts.

- Partially Audit: Kokomo Finance’s audit report only covered the token contract, rather than the protocol at large. Euler Finance introduced vulnerable code

EToken.sol:donateToReserve; however, Omniscia only performed an audit of the Chainlink integration component. - Use Unsafe Vanity Address: Wintermute used the Profanity tool to generate addresses with multiple leading zeros. The private keys were compromised by brute force.

- Rug Pull: A member of Hope Finance deployed a fake router and deceived the other three owners into approving a multi-signature wallet, thereby siphoning off the funds. Merlin DEX directly inserted a backdoor into the contract. Certik did indeed raise this trust issue in their audit report, but Certik marked it as resolved without the code being genuinely fixed.

The practical value of an audit becomes limited when a project is unable to effectively prevent human errors. This highlights the need for rigorous processes to prevent human errors and oversights. The next section will propose some prevention methods.

Analysis of Layers, Loss, and Occurrences

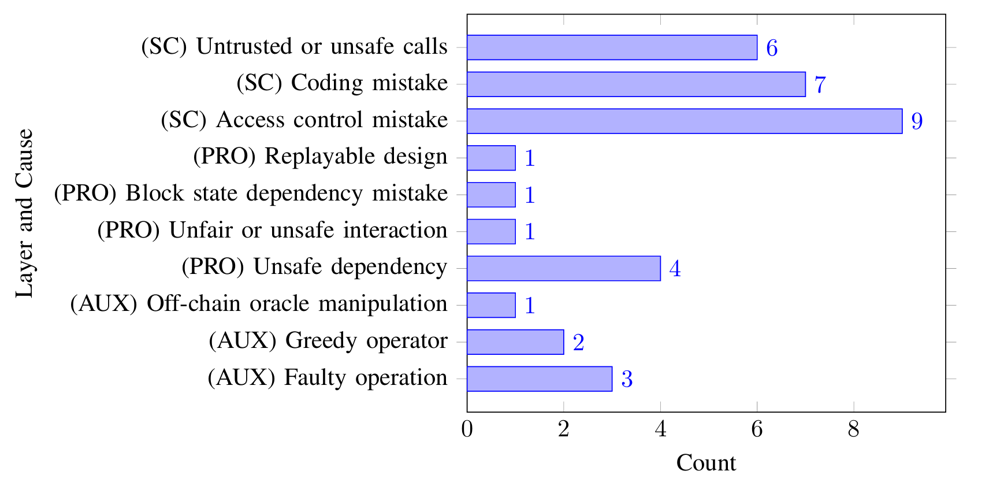

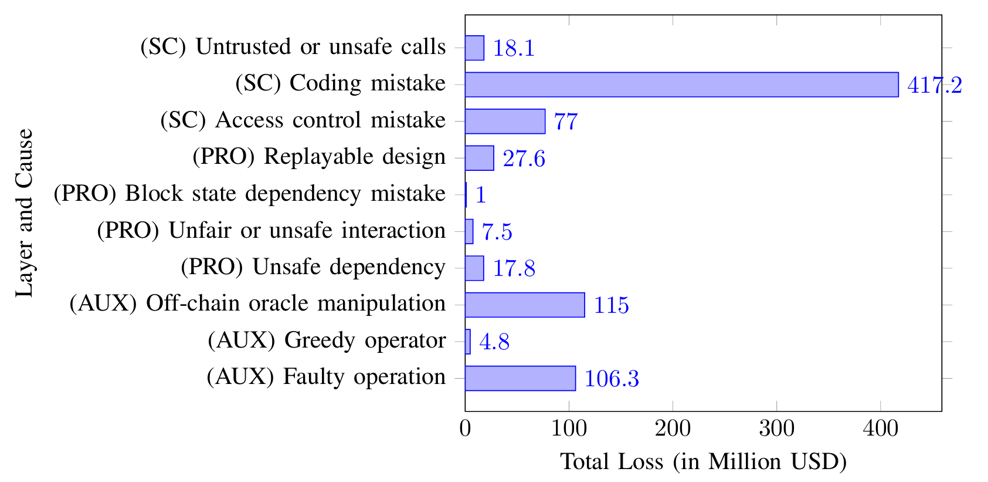

Table III presents the losses, occurrence frequencies, and average losses of individual layer attack events. It is noteworthy that neither NET Layer nor CON Layer was involved in the 35 incidents. This observation suggests a higher level of security in these layers, making it challenging for attackers to target them. The most common incident causes belong to SC Layer, accounting for 22 out of 35 cases (62\%).

Figure 1 shows the frequency of incident causes. In SC Layer, Access Control Mistake is the most common incident cause. Most of the victims deployed flawed authentication logic when updating new contracts. In PRO Layer, Unsafe Dependency is the most common incident cause, which implies that DeFi projects should not blindly trust external data sources, such as oracles. In AUX Layer, Faulty Operation and Greedy Operation are common causes. Preventing the leakage of private keys and guarding against rug pulls are critical aspects of security in this context.

Figure 2 shows that the losses incurred due to Coding Mistake in SC Layer significantly outweigh those caused by other factors. The losses in the AUX Layer are also substantial. The losses incurred by these vulnerabilities are exceptionally costly. Even a single occurrence of such a vulnerability event could result in the flourishing project’s bankruptcy.

Security Strategy and Conclusion

- while the majority of DeFi projects undergo professional audits, certain key issues, such as human error and oracle manipulation, are not solved. The future development of DeFi security may involve the establishment of rigorous operational standards.

- Improving the collaboration model between DeFi developers and auditors has the potential to enhance the reliability of audits.

- SmartBugs incorporates 19 open-source static code analyzers. We selectively utilized four: Mythril, Manticore, Slither, and Solhint to analyze some victims. Unfortunately, none of these tools successfully detected the vulnerabilities causing the incidents. Hence, there is still substantial room for improvement in existing code analysis tools.

Comments powered by Disqus.